After a morning spent discovering the subtleties of the tea ceremony, we went to the strangest and least known island of the Seto Inland Sea (at least in that part of the sea, I don’t really know anything about the western part), I mean Ōshima. There are several islands with this name in Japan or even in the Seto Inland Sea, after all, Ōshima means “Big Island” except that very often, islands with this name are not that big at all, just like the one I’m going to talk about today, the Ōshima that is located in the Kagawa Prefecture. It’s actually the smallest of the seven islands taking part in the Setouchi International Art Festival. However, just like the six other ones it deserves to be more known and learned about, but for very different reasons.

Since 1909, Ōshima has been a forbidden land to the general public as the whole island became a sanatorium under the name of Ōshima Seishoen Sanatorium , housing people affected by Hansen’s disease, a disease better known under the name of leprosy. At that time, Japan voted a law forcing anybody affected by leprosy to be confined in sanatoriums in various places around the country. The law was repelled in 1996 only! Long after the disease was studied, understood (it’s not really contagious, contrarily to popular belief) and that a cure had been found for it.

Despite that, the sanatorium still exists and is still open for the simple reason that it has become the home of the former patients that have nowhere else to go, most of them being very old, more or less disabled and having no family left that they know of or that would have them.

Today, there are 104 former patients still living on the island, as well as some staff members who stay there for longer or shorter periods of time. The residents average age is above 70 years old and most of them have spent most of their lives on the island that is today their universe, unable to leave it before 1996 and very rarely doing so ever since.

Thanks to the Setouchi International Art Festival, the island has opened its doors to the public for the first time, but don’t hope to go around exploring every nook and corner searching for more or less hidden works of art like one could do on the other islands. The residents’ privacy comes first. As it’s the first time outsiders are allowed to come to the island, it is important that the lives of the residents not to be turned upside down by a large influx of visitors and because of this, there were only three boats a day that went to and from the island, and most of the visiting was done on a guided tour. The good side of having a guide is that he gets to tell you about the island’s very particular history. The bad side is obviously the lack of freedom in visiting the island (but who would be so selfish to complain about that on this island where people have been denied freedom all of their lives and for no particular reason than fear and ignorance?) as well as the fact that if you don’t understand Japanese, you’re basically screwed. Thankfully 康代 could translate parts of what the guide explained, and thankfully, Cathy Hirano has a great blog where she explains some of the things I missed.

One of the most interesting thing during the visit was the fact that we got to meet this charming old man who was hoeing his small garden full of wonderful Bonsais and who told us a little bit about his life (picture link source: Koebi-Tai). It was somewhat sad that we were not allowed to film the residents of the island, his story deserves to be put on film so that people can learn about it. As I’m typing this, I remember that some film was being shown, with residents talking, on a screen in one of the rooms we visited. I wish it were available somewhere. Maybe it is. Who knows?

Here is what I understood of this man’s story. He was diagnosed with Hansen’s disease when he was 16 (if I understood right, he’s 65 today) and he’s been living on the island ever since. He told us how, in his youth and as he was not very sick (nothing in his appearance indicated that he had been sick, except for one blind eye), he had to help the undermanned staff taking care of people that were much more affected by the disease than he was. Yes, he was a patient, and he had to work (most likely for free) taking care of other patients. Another example of the unjust life he had been forced to live. He also underlined the fact that now he’s free to leave the island, but he has nowhere to go, he has no family and everyone he knows on this planet lives on the tiny island that has become his world.

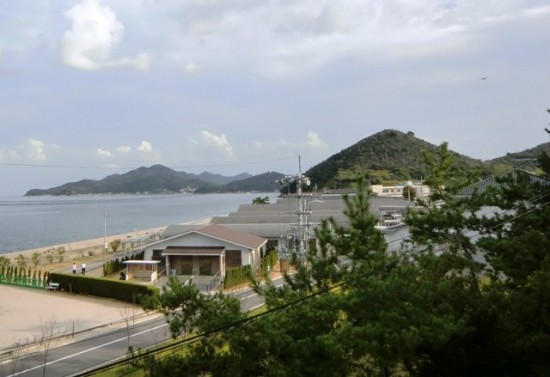

And indeed, this island is a world in itself. It doesn’t look anything like any of the other islands in the area, buildings are all very functional, nothing traditional in them and the atmosphere is quite unreal, almost eerie. The parallel I couldn’t help but draw was with the Village from the British show the Prisoner. Same unnatural feeling, for example, there are loudspeakers, along every street on the island that play a very quiet and soothing music as if the goal was to make sure people stay calm and tamed (the real reason is more benevolent, it’s to help blind residents locate themselves). A few residents rode their bike here and there, obviously as curious about the visitors as the visitors were about them and their island. Every time they’d be near enough, they would utter a friendly and assertive “Konnichiwa.” Despite what we were told about protecting the privacy of these people, all I could see in their eyes was happiness to see new people for once (although, I have encountered only 5 or 6 residents, I can’t talk for the 99 or so others).

For the festival, this former welcome center for the patients’ families has been turned into Café Shiroyu, a place for both visitors and residents, so that they can meet and enjoy food and drinks together. Unfortunately, it’s not always open and was closed when we were there.

NHK was there, shooting a piece about the island. Here, they’re interviewing project director, Nobuyuki Takahashi, who organized the various installations made by the residents to tell the visitors about life on the island.

I left the island in a strange mood. Not sad, not shocked. Just strange. That place being so depressing and fascinating at the same time. A strange feeling of waste – waste of human lives – came out of this visit, but at the same time all of the residents I encountered seemed happy and content, despite their old age, their disabilities and the fact that they spent most of their lives as outcasts and prisoners.

I really hope to get back there someday, although I’m afraid that now that the Festival is over, possibilities to go to the island are scarce. Unless, the festival did change things. I don’t know.

(edit: since the Festival has ended, the island remains open to the public two days a month, I publish which days along with the Art Setouchi schedule every month)

If you want you can also check this post showing pictures of Ōshima in 1931.

[iframe: width=”550″ height=”550″ frameborder=”0″ scrolling=”no” marginheight=”0″ marginwidth=”0″ src=”https://maps.google.com/maps?f=q&source=s_q&hl=en&geocode=&q=Kagawa+Prefecture,+Japan&aq=0&sll=37.0625,-95.677068&sspn=58.076329,131.396484&vpsrc=6&ie=UTF8&hq=&hnear=Kagawa+Prefecture,+Japan&t=h&ll=34.406945,134.105086&spn=0.019474,0.023561&z=15&iwloc=A&output=embed”]

View Larger Map

Discover more from Setouchi Explorer

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

For more information about Oshima, I really advise you to read Cathy Hirano’s blog, especially the posts dedicated to the island, they may just be the best source of information there is on this island available in English on the web:

https://cathy.ashita-sanuki.jp/e278607.html

https://cathy.ashita-sanuki.jp/e335742.html

https://cathy.ashita-sanuki.jp/e342887.html

Some people actually suggested that HIV patients be treated the same way i.e be outcasted to somewhere no one wants to go. 🙁

In France too, some right wing leader suggested that back in the 80’s. Thankfully, it was met with lots of antagonism at the time (and the guy never had any power anyway).

Many thanks for this interesting post. As I’m going to Japan for the first time soon, I want to know as much as possible about the country. So I’m reading a book on the Seto Inland sea by Donald Richie. The chapter on the Oshima leprosy sanatorium really touched me. Thoughts about people who were excluded from the society for whole life (even if cured!) because of stigma really made my heart ache! A week after finishing the book, it is still on my mind. So, I have searched the internet to know of what has become of this place now. It is a most surreal feeling to realize that some of the people Richie described in his book fifty years ago may still be alive on the island. At least, I’m happy for them as they seem to be happy, living peaceful life. Still, I can’t get over the feeling of great injustice. It’s like, you mention, “waste of human life”. Fifty years ago seems like a prehistory to me (I’m 32). Realizing how the world has changed since then, it seems surreal that people were isolated from the broader world on this tiny island for such a long time. I can’t help but feel sorry for them, even if I shouldn’t.

Donald Richie’s book is a great book, and reading it nowadays is an interesting experience, as many things have changed a lot since the time he wrote it, and some haven’t changed at all.

Oshima is one of those places. Depending on when you’ll be here, you may be able to visit the island. During the Setouchi Triennale, it’s open to the public every day, but outside of the Triennale, it’s only open about one week-end a month.